December 7, 2022

The first large diamonds were found by hand. It will never happen again.

The dream of such jewels would fuel the mining industry for decades to come.

The first diamond over 1000 carats ever recovered was the Cullinan Diamond, and it was picked up off the ground of a mine in South Africa. The diamond created from that stone – well, one diamond of the nine diamonds cut from the original rough stone – is the highlight of the British Crown Jewels. The rough stone that came up was over 3 100 carats – for the next 100 years, no larger diamond would be found, but it was nonetheless a turning point: diamonds that big existed. Simple as that. The dream of such jewels would fuel the mining industry for decades to come.

"A hole in the ground into which you throw money."

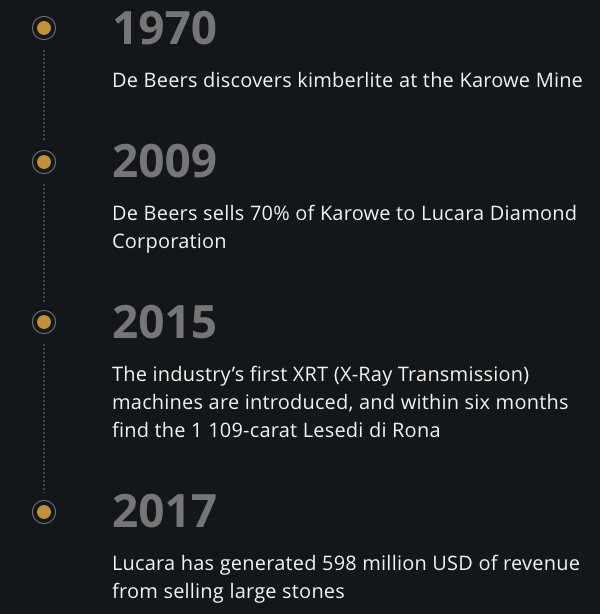

Like many great success stories, Lucara’s Karowe diamond mine in Botswana started… as a failure. Diamond giant De Beers purchased rights in 1969, before concluding that the kimberlite found in 1970 wasn’t viable to mine. In 2009, they sold their stake in the mine, 70%, to Lucara Diamond Corporation in Canada. Lucara was founded by the late Lukas Lundin, Eira Thomas, and Catherine McLeod-Seltzer, with goal of creating an Africa-focused diamond exploration and mining company. It took until 2014 for Lucara to implement a new method of mineral processing through ore sorting – also known as 'SBS'. Using XRT – short for 'X-Ray transmission' – Lucara began to discover some of the biggest diamonds ever found.

Finding diamonds means destroying diamonds.

Such prizes (and the corollary profits) drove innovation and evolution in the mining industry – at the beginning, it was manpower and explosives. While today’s mines see far fewer people on the job, the process is still violent – to extract rock, you’ve got to explode it. Explosion after explosion – that’s the sound you’d hear if you were in the right place at the right time at a diamond mine. That’s why it would be nearly 100 years before someone would find another large diamond – because most of them were getting destroyed in the process of trying to recover them. In fact, it’s almost certain – the largest diamonds that ever got pushed up from the earth's mantle to the earth’s crust have most likely been destroyed. But – as our own Geoffrey Madderson says, it’s a “ghost in the machine” – it’s always impossible to tell where in the process a diamond is being destroyed. So – it’s best to try and catch the big stones as early as possible.

In fact, it’s almost certain – the largest diamonds ... have most likely been destroyed.

The modern diamond mine is a machine.

Diamond mines are so big it’s tough to think of them as a singular ‘machine’, but in fact, that’s exactly what they are – a network of systems, with input and output, requiring calibration and maintenance to run smoothly. When we at Stark think of designing a mine, we’re not selling a part or a tool – we’re building an entire machine.

His name was John Armstrong*

The ‘big dogs’ of the diamond mining world knew how it worked, right? They’d built the industry. They’d made it work for years. Many had gotten rich, and a few had gotten very rich. Incentive to change? Small.

Lucara Diamond was not a big mining concern – in the mining world, Lucara was effectively a startup – and while they knew how diamond mining worked, they also had ideas about how it could work. In 2013, they hired Dr John Armstrong, a Canadian known for his skill in geology and evaluating deposits. In 2014 John and other senior management and executives sat in a room of 50 process engineers – and told them the way they’d been looking for diamonds was all wrong – and they wanted to make a bet. On big diamonds. Fortunately, they listened.

* No relation to the astronaut, but in our offices, we do like to refer to him as ‘Major Tom’.

Short-circuiting diamond recovery.

Since mining is about volume, it is also, by nature, about efficiency. Any way to make any part of the process cheaper, faster, simpler is an improvement. XRT was the chance to tighten up the system and skip dense media separation. It also required less water, less energy, and less manpower.

Speed + Accuracy.

Digging diamonds out of ore is a numbers game – the more raw material you can process, at less cost and effort, the more money you can make digging up diamonds. But it’s not just about speed – it’s also about accuracy. Going faster isn’t going to help if you’re throwing diamonds out with the rubbish – or destroying them.

Value preservation

The logic went like this: in 2013 at Karowe diamond mine, four diamond fragments of significant size were recovered. In the lab, it was confirmed – the four pieces had started as one. If there was one, there was likely more – but they were being destroyed into smaller fragments before they were discovered.

Old school diamond mining had a variety of methods, but it usually went like this: blast it out of the ground – politely called ‘liberation’ – crush into a manageable size, use a variety of other methods – putting the raw material into a slurry to sort by using DMS (Dense Media Separation), or chemically reducing the surrounding ore, to sort it all out and hope for the best. Slow, cumbersome, resource intensive – but reliable for finding small diamonds. But in the diamond industry, the big money is made on the big stones. For most firms, ’specials’, usually account for 5% of production and may in several instances account for over 60% of the value.

John Armstrong:

“In the middle of November 2015, we recovered a 1 109-carat stone out of the LDR. It was the first 1 000+ carat diamond recovered in over 100 years, and the first one recovered in a modern, commercial plant. Mechanically separated using ore sorting. 65 x 56 x 40, a beautiful, gem-quality diamond. It still had some material adhering to it, but you could see: this was a gem. So of course, we’re all pretty happy about that."

"Then the next day, we recovered an 813-carat diamond out of the same box. So in the course of two days, we recovered two of the largest gem quality diamonds that had ever been recovered as rough stones. And the quality of those diamonds was without reproach. These were most definitely high gems.

Ultimately, the 813-carat diamond sold for the most that a rough diamond has ever been sold for, at 63 million USD. And then the 1 113-carat diamond, after cleaning, ended up being sold for about 53 million USD. So those two diamonds, in one short period of time generated over 110 million U.S. dollars of revenue for the company."

$110 Million in two days

Invisible tools, visible Benefits: How XRT Works

The most important parts of an XRT machine aren’t even visible. It’s the broad band radiation that detects the diamonds based on their atomic number of 6. This has proven to catch 98% of diamonds that go through the XRT process. The next invisible part of the process? A puff of air, which moves a confirmed diamond off the belt and into the glove box. The wild thing? XRT technology had been employed at mines for years – as a security measure to check that no diamonds were being removed off property. But it took a shift in thinking to understand the technology had other uses.

"The diamond mining industry started early with people literally digging and sorting by hand, and over time there was an evolution to modernised recovery processes. Through that, a lot of research was done and processes were developed, as well as understanding and technical competence – but that long standing history actually blinds people to look at things like a startup."

MINING = STARTUP.

"The evolution – focusing on first principles, understanding that it’s possible to separate the goal from the already established process – let Lucara approach mining like a startup. Prior to the success at Karowe, preventing breakage was a problem that had plagued the industry for years. Millions of dollars in value were created - not just by digging through some work, but through process optimisation and the smart application of new technology – and that’s what we do at Stark."

Dig deeper with our Large Diamond Recovery white paper!

Want to know more about kimberlite, size-frequency distribution, and learn what makes sensor-based sorting actually work? Dive deep into our Large Diamond Recovery white paper to gain a thorough technical understanding of Stark’s process optimisation methodology.